Stewardship, 22 October 2017

Introduction

I’m delighted and honoured to have been invited to share some thoughts with you this evening.

Thank you, Rev Michael, for that opportunity. I’ve been asked me to talk about stewardship, a term which can mean many different things to different people.

For me, stewardship is an individual responsibility; a collective responsibility, and a moral responsibility that crosses borders and applies to us all.

We are all custodians of our planet, our home, irrespective of our background and beliefs.

Just this week, many of you might have noticed the eerie red skies above Brighton and Hove, and elsewhere. The Argus reported the ‘phenomenon’ as being ‘like Armageddon’. Thankfully, they were wrong on this occasion. But the red skies on Monday afternoon do serve as a reminder, that land borders are irrelevant when it comes to the environment.

We are all connected by the simple fact that we share a planet – so dust from the Sahara; the impact of Hurricane Ophelia; and debris from forest fires in Iberia; matter. As does our own imprint on the environment closer to home – the waste we produce; the pesticides we use; the everyday choices we make.

So I want to talk about stewardship of our planet – in particular in the context of the greatest threat we face today, climate change – and the question I want to ask is how do we mobilise people to finally take action to protect our planet, our precious and our only home.

Because time is running out.

The evidence of the accelerating climate crisis is all around us, and yet still we fail to act.

You may remember a film that was made almost 10 years ago now, called the Age of Stupid.

It’s based on the premise that following some kind of climate catastrophe in around 2050, there is one sole survivor, played by incomparable and much-missed Pete Postlethwaite.

And in the film, he looks back to now, at reels of television footage, real footage from weather events over the early 2000s

- the typhoons in the Philippines

- the heat waves in Australia, the freezing temperatures in the US

And he says – in words that still make the hairs go up on the back of my neck:

Why is it, knowing what we knew then, we didn’t act, while there was still time?

And that seems to me to be, quite literally, the most important question of our time.

It quite literally haunts me.

Why is it that we appear to be content to go down in history as the species that spent all its time monitoring its own extinction, rather than taking active steps to avoid it?

And it seems to me that it is, at least partly, because we’re afraid to go there.

We’re understandably afraid of the darkness that might engulf us if we do.

How do we cope with the thought that humanity may not wake up in time?

That climate change might become irreversible?

That societies, even in the developed world, might no longer have the ability to respond or cope?

The magnitude of the crisis is so huge, and the challenges of tackling it seemingly so enormous, it’s overwhelming – and the only rational response can sometimes seem to be to go down the pub and try to forget all about it.

Climate Crisis

Our failure to act can’t be because we lack the evidence of what’s happening all around us, that we lack the facts.

We know that last year was the hottest year on record

The previous record was set in 2015; the one before in 2014.

15 of the 16 warmest years have occurred in the 21st century.

Arctic sea ice covered a smaller area in winter 2015 than in any winter since records began.

India has been hammered by cycles of drought and flood.

Southern and eastern Africa have been pitched into humanitarian emergencies by drought.

Wildfires storm across America; coral reefs around the world are bleaching and dying.

And just a few months ago, in Canada, due to intense glacial melting, the course of an entire river shifted – the Slims River, once full of life and energy, simply vanished.

So it isn’t that the evidence isn’t there. So why don’t we act with a sufficient sense of urgency?

There are lots of reasons.

The power and vested interests of the fossil fuel companies, who are increasingly not simply lobbying Government, but being given senior roles within it.

Or that people are just too busy trying to get by; Trying to cope with the latest obscenity from a government that is intent on making the poorest and most vulnerable pay the highest price for an economic crisis not of their making; trying to keep a roof over their heads, while housing benefit is cut; trying to live a dignified life, while disability payments are being slashed.

Or that we’re being bombarded by hundreds if not thousands of advertisements each day, all of them trying to persuade us to go out and carry on consuming.

In Professor Tim Jackson’s eloquent words, to spend money we don’t have on things we don’t need to make impressions that don’t last on people we don’t care about.

So lack of progress on climate change is caused by this mixture of vested interests, political paralysis and civic ambiguity. All of that is doubtless true

But I’m going to suggest that another crucial part of the reason is that we don’t dare feel what climate change is truly about.

Academically, theoretically, we know about the dangers of exceeding 2 degrees warming

But we rarely have the time – and the courage – to overcome fear and to connect emotionally with that reality.

I’m struck by the phrase that we won’t protect what we do not love.

The American author Richard Louv puts it like this:

“We cannot protect something we do not love, we cannot love what we do not know, and we cannot know what we do not see. And touch. And hear.”

And that’s why giving people – particularly children and young people – the opportunity to see, to touch, to know and ultimately to love the natural world around us – is so incredibly important.

The author Zadie Smith has written about how it is this love which spurs us to action.

And she does it so beautifully in an article in the New York Review of Books, that I hope you don’t mind if I quote quite a long passage of what she says:

“There is the scientific and ideological language for what is happening to the weather, but there are hardly any intimate words. Is that surprising? People in mourning tend to use euphemism; likewise the guilty and ashamed. The most melancholy of all the euphemisms: “The new normal.”

“It’s the new normal,” I think, as a beloved pear tree, half-drowned, loses its grip on the earth and falls over.

The train line to Cornwall washes away—the new normal.

We can’t even say the word “abnormal” to each other out loud: it reminds us of what came before.

Better to forget what once was normal, the way season followed season, with a temperate charm only the poets appreciated….

We always knew we could do a great deal of damage to this planet, but even the most hubristic among us had not imagined we would ever be able to fundamentally change its rhythms and character, just as a child who has screamed all day at her father still does not expect to see him lie down on the kitchen floor and weep.

Oh, what have we done! It’s a biblical question, and we do not seem able to pull ourselves out of its familiar—essentially religious—cycle of shame, denial, and self-flagellation.

This is why the apocalyptic scenarios did not help—the terrible truth is that we had a profound, historical attraction to apocalypse.

In the end, the only thing that could create the necessary traction in our minds was the intimate loss of the things we loved. Like when the seasons changed in our beloved little island.”

So it seems to be that part of what we need to do – to plant love.

And through love, we plant hope.

And hope is a renewable resource.

Not hope as in wishful thinking, not hope as in having your fingers crossed behind your back, not hope like sitting on the sofa clutching a lottery ticket.

But radical hope – hope that changes things.

Because you love them enough to connect with them, and to imagine a different, better future – and having imagined it, having that compelling vision of how things could be – you work to achieve it.

I hope you’ll forgive another quotation from another favourite author and activist Rebecca Solnit:

“Hope is an axe you break down doors with in an emergency; because hope should shove you out the door, because it will take everything you have to steer the future away from endless war, from the annihilation of the earth’s treasures and the grinding down of the poor and marginal.

Hope just means another world might be possible, not promised, not guaranteed.

Hope calls for action; action is impossible without hope.”

So armed with hope, perhaps we too can move through what Zadie Smith calls the elegiac what have we done to the practical what can we do?

So I want to end by calling people to action today.

Remember what you love – and do all you can to fight for it.

And of course there are reasons to be hopeful:

Last year was the hottest year on record – but it was also the year that:

- Portugal ran entirely off renewable energy for 4 consecutive days

- The number of solar powered homes in California topped 6 million

- Volunteers in India planted 50 million trees in 24 hours

- At Standing Rock, Native American climate change heroes halted construction of the Dakota Access oil pipeline

- And, for the first time in 100 years, the number of tigers in the wild increased.

And another reason for hope is the growing realization that the changes we need to make in order tackle the climate crisis, and to learn to live more sustainably, are positive ones in their own right.

This isn’t about hairshirts or shivering around a candle in a cave. They would be good things to do, even if we didn’t face a climate crisis.

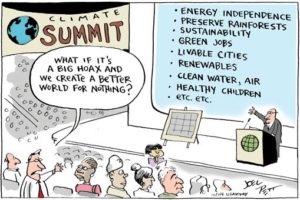

by cartoonist Joel Pett

One of my favourite cartoons is of a Professor in a lecture theatre, standing in front of the whiteboard.And on the whiteboard she’s written up all the advantages of creating a zero carbon economy:

- Properly insulated homes

- Fewer people living in fuel poverty

- Local healthy food systems

- More time out of the office

- More affordable public transport

- Kids playing in the streets again

And one of the students has their hand up and the speech bubble says:

“But what if climate change is a hoax, and we’ve made a better world for no reason?”

When Rev Michael invited me to join you, he explained that the Village MCC is made up of just a small group, but his description painted a picture of an impressively active and community-minded group of volunteers.

Which is why I was so happy to sneak across the constituency border and join you this evening.

In recent years, with issues like rough sleeping ever more present, and the repercussions of welfare reform being felt by so many – I never cease to be impressed by some of the church communities we have in the city, who do so much to support those facing hardship. It does make a difference, and it does lead by example

Making a better world is why we’re here.

Planting love and reaping hope.

Stewards of this our precious and only home.

Recognising that we – all of us – are the people we’ve been waiting for – and that all of us can make the difference.